In the course of implementing Agile practices, an organisation is likely to come face to face with deficiencies in both IT and business operations. Shortcomings in specifications, in quality, in team capability, in technologies all quickly come to the fore. Agile practices allow us to not only identify these shortcomings, but to call them out in a fact-based manner.1 Still, how people in an organisation respond when presented with these will determine how successfully it adopts Agile practices.

While in theory, decision-making in a business context is coldly rational, decisions made by people in business usually are not. Because they impact people, business decisions – especially where performance or results are concerned – can be highly emotional. With regard to adopting Agile practices, this creates an important consideration. While they lend themselves to tremendous transparency, that transparency can unintentionally create discomfort and embarrassment. One person's "liberation" is another person's "fear."

The reaction to this increased transparency is very much an organisational characteristic. In the November-December 2006 edition of World Business, James Bellini writes:

- Businesses behave like people… the nature of this behaviour gives us vital clues as to the condition of a company’s underlying psychological state and in so doing helps us identify those that will succeed and those doomed to fail. It also offers the means by which those confronting failure because of an ailing, dysfunctional psyche can be given a new direction, towards revival and profitability.2

Mr. Bellini makes the point that organisations can fail because they fool themselves into believing something to be true, no matter the facts. There is an important alert here for those wanting to inject Agile practices: organisational self-delusion can be an obstacle to injecting fact-based management. Clearly, we’ll struggle to inject facts if facts don’t have currency. More constructively, there is clearly a “healthy” approach to presenting facts, as opposed to an “unhealthy” approach of confronting with facts.

The business sponsor and implementers of an Agile “programme of change” must be able to honestly assess the following:

- How well do people understand and accept the problems the organisation faces today? Do they see, for example, a deficiency in scalability materially impacts bottom line profitability? Do they see long development cycle times as interfereing with customer responsiveness and, therefore, new business? Do they look for and recognize features in competitive products as disadvantage in the market? Or is the prevailing attitude that the company have its customers, and the competition have its customers, and it will just sort itself out in the end?

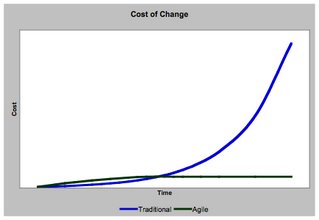

- To what extent do people tolerate and encourage risk, and to what extent can the organisation accept fast failures? The initial adoption of Agile involves a lot of experimentation, trial-and-error, learning-by-doing, and failure. Is the organisation risk-averse with a “shoot the messenger” culture when things don’t quite turn out as planned? Or is there a recognition of the benefit to continuous learning and “fast failures.”3 Specifically, is there an expectation that people are in "stretch roles" learning and honing their capabilities as individuals? Is there greater infrastructure - training, mentoring, coaching - to support this?

- Is there a culture of responsibility or a culture of blame? Exposing problems will make people react, one way or another. For example, many companies are burdened with highly manual processes. Staff changes through resignation or promotion disrupt these processes. Do people accept the natural turbulence of transition and look for constructive ways to create more durable solutions? Or do they simply pass around blame for work not done?

- Finally, with what discipline do we take project sponsorship decisions? That is, how disciplined is our project portfolio management? Can we accept a project’s actual cost, time and trajectory in the context of a business case, and take necessary action? Do we accept reporting the actual state of a project as an expression of mastery of our profession? Or are go/no-go decisions substantially rooted in non-business factors, the team's credibility intertwined wth a delivery commitment, and hope the fundamental strategy for a project to maintain course?

Further complicating matters, each of these are bi-directional. The manner in which we expose problems – confrontational or progressive – will contribute to the success of the programme of change. That is, there must be a constructive, as opposed to a destructive, language for change. The responsibility for creating this positive nomenclature lies with the instigator of change.

Collectively, this sounds "soft," and perhaps it is. But at the end of the day, management is still “getting things done through people.” Not money, not technology, but people. We understand intuitively that these things matter, whether we can measure them or not. “Soft” or otherwise, they are relevant to us as managers. And references abound.4

The first example comes from Ford Motor's recently initiated turnaround. A recent story in the Wall Street Journal pointed out that Alan Mullaley, CEO of Ford Motor, openly applauded a division head for owning up to poor performance in a senior staff meeting. Mr. Mullaly’s reasoning? You can’t solve problems if you don’t acknowledge them, and not enough people were acknowleding them when Mr. Mullaley arrived. Something to think about in this example, too: if this is what's happening at the most senior levels of the company, what makes us think it will be any different within a project team?

The second example is Scuderia Ferrari F1. In an interview with F1 Racing Magazine, Ross Brawn, the recently retired technical chief at Ferrari, described team decision-making as:

- "Every last detail is critical… You cannot be weak in the tangibles, like the design of the car, and you cannot be weak in the intangibles, like your … interpretation of the rules. Whatever you felt you could achieve you’ve then got ot go out and find another 10 per cent…. We all knew that we had to do it and we knew the other guys were doing it, so that if you were not doing it you would be letting the side down. It was great to be a part of that mind-set; a group where we were all giving absolutely everything."5

Albeit extreme, there is a lot to be gleaned from this as an instantiation of organisational psyche. The cultural norms, the expectations of the peer group, while soft, are unambiguous: push yourself to the limit to push the platform (e.g., the car) to the limit. Leaving the potential for competitive advantage on the table due to lack of effort was unacceptable.

Clearly, Scuderia Ferrari is an organisation that deals in facts, not excuses or justification. Somebody will ask as a matter of fact, and not accusation: did we perform every combination of performance and reliability test? Are we in compliance with the sporting rules of the FIA? You don’t want to be the person called out for not answering those questions to their fullest; the organisational psyche guides you to fully pursue these answers prior to facing the questions.

The bottom line: organsational “psyche” is a factor in our ability to change and respond. Ultimately, it impacts our fundamental ability to compete. Mr. Brawn: “'It’s very rare in modern F1 to come up with a dramatic new concept or idea that will give you a step change in performance. So you cannot give anything away.'”6 This is not accidental, but systematic, part of the landscape. It might initially read a defensive tactic, but it’s very much an offensive strategy. Thoroughness means we don’t leave anything on the table; aggressiveness means we find and maximize innovation. That makes an organisation able to accept the need for change, and implement that change. And that makes it more competitive.

1I am indebted to David Pattinson on this point. In the course of an engagement some years ago, he very specifically made the point that we hadn’t established a basis of fact for an issue, and we risked escalating a problem to a client “as a matter of opinion and not as a matter of fact.”

2Bellini, James. “Disguises and denial” World Business, November-December 2006. There’s a lot of information in his article, it’s worth re-reading a few times to get the full extent of his messages.

3It’s worth mentioning that Gartner has called out “fast failures” as a principle for effective innovation: “Fail Fast for More Effecitve Innovation.” Gartner Research. 1 March 2006.

4Oddly, and hopefully coincidentally, both are automotive.

5Allen, James. “Ciao for Now, Ross.” F1 Racing, January 2007. There’s a full quote from Mr. Brawn that truly captures the essence of Ferrari’s F1 team. Go buy the magazine.

6Ibid.